The Times, 15 November 2010

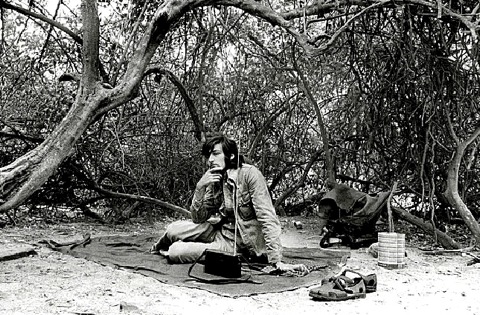

Jon took this self-portrait while being held by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front during September 1976

Little is so full of spine-chilling menace as being held hostage by armed rebels in the African desert. In your lowest moments you believe that your captors will as soon shoot you as look you in the eyes. That is how it would have been for Paul and Rachel Chandler, who were kidnapped by Somali pirates as they sailed off the Seychelles.

In 1976 I was kidnapped in northern Ethiopia and held for three months. Loneliness and isolation were as much an enemy as the hostile environment and I suspect that they were an enemy for the Chandlers too.

Some of their messages addressed their fear that they might die and that no one cared. I can understand. The feeling that one might die alone and invisible, be struck off the book of life in a remote corner of the world, is the most dispiriting sensation of all.

I kept myself going with thoughts of freedom and of seeing loved ones again. Anticipating that moment is one thing. Dealing with it when it comes is quite another. Absolute freedom after a long time of isolation tinged with moments of danger and fear takes a period of readjustment.

The initial glare of publicity makes you feel special. When it fades, as it quickly does, you feel once again abandoned. There was no escape from having to get on with dealing with the day-to-day trivia of a life to which I thought I might never return.

The only way was to try to learn from the experience. I told myself that if I could cope with waking up each morning a prisoner in the desert then I could cope with anything.

Examining my life while in captivity, I thought hard about the errors I had made and cringed at things I had done. I wanted, on release, to put everything right. It was not possible. My advice to the Chandlers is: gently does it.

The reality of sudden freedom is not straightforward. Life is simple as a captive. There are no choices to make; they are all made for you. Release means an onslaught of choices. In my case, there was a great deal of self-questioning as I tried to work out how to use this great gift of life that had been returned to me. Also, in captivity I had glimpsed the miserable lives of my captors and, while I deplored their action, I gained some understanding of what had driven them to it. Coming back to my comfortable Western existence I felt sometimes uneasy, even guilty.

The truth is that you never actually do get over being kidnapped. It carries on shaping your life. This was brought home to me when, last year, I met my kidnapper, a guerrilla leader, 34 years after he had abducted me at gunpoint.

It is ironic that the Chandlers, who embarked on their retirement with a dream of being free on the seas, should have learnt, through being kidnapped, the complexities of what freedom actually means.